Sponsored by MTAC, Santa Clara Branch

About

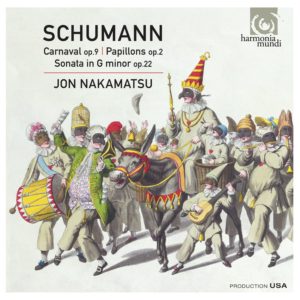

San Jose native and Stanford graduate Jon Nakamatsu achieved international attention with his 1997 Gold Medal triumph at the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition. Extensive recital appearances include Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, and the Kennedy Center, as well as premier venues in Europe, South America, and the Far East. His CD featuring Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue and the Concerto in F hit #3 on Billboard’s classical music charts. In 1999, Mr. Nakamatsu performed at the White House for President and Mrs. Clinton.

Program

- C Minor (Allegro molto moderato)

- E-flat Major (Allegro)

- G-flat Major (Andante)

- A-flat Major (Allegretto)

- Allegro

- Andante

- Scherzo: Allegro molto e con fuoco

- Allegro con fuoco—Presto non troppo ed agitato

Program Notes

The title impromptu suggests—but does not mean literally—music made up on the spot. The term had been created in the early 19th century and used most memorably for Schubert’s eight impromptus for piano. But one should be wary of that title, which implies an atmosphere of casual, almost improvisatory music-making—such an impression of spontaneity and ease is usually achieved by a great deal of work and revision on the part of the composer.

This was certainly the case with Chopin, who wrote four impromptus. The Impromptu in A-flat Major dates from 1837, when he had been in Paris for six years and had just come to know the novelist George Sand—their sometimes stormy relation would begin the following year. This impromptu is notable for its complexity and difficulty: Chopin revised the music repeatedly as he wrote it, and it demands a pianist of formidable technique. It also goes like a rocket: the marking is Allegro assai, quasi presto, and the effect of the rippling triplets in both hands has been compared by many to the impression of sunlight sparkling off the surface of water. The middle section brings a change in rhythm and atmosphere. The restless triplets vanish, and in their place Chopin offers a noble if subdued melody that grows more animated as it proceeds; at its most dynamic, it takes on something of the quality of a cadenza and suddenly plunges back into the triplet rush of the opening. After all this sparkling energy, the close is surprisingly subdued.

Chopin composed his Impromptu in G-flat Major in the fall of 1842, dedicated it to one of his students, and published it the following year. This impromptu is one of the works that Chopin played at his infrequent public performances. It is in the expected ternary form, yet it has the spontaneous manner that should characterize a work called “impromptu.” The opening bears some resemblance to the opening of the famous Impromptu in A-flat Major: both begin with an energetic rush of triplets. Chopin marks the present work Presto; and it does move speedily, though without a suggestion of agitation. The transition to the central episode, in common time, is done quite subtly: Chopin has already begun to accent the original 12/8 meter as if it were 4/4, and the arrival of the middle section feels completely settled. This sostenuto central section is unusual because Chopin gives the noble melody entirely to the left hand, while the right accompanies; the transition back to the opening tempo is made just as subtly as the first transition.

Schubert wrote eight impromptus for piano during the summer and fall of 1827, probably in response to a request from his publisher for music intended for the growing number of amateur musicians who had pianos in their homes. This music is melodic, attractive, and not so difficult as to take it out of the range of good amateur pianists.

This program offers the four impromptus Schubert wrote late in the summer of 1827, only a year before he died; the first two were published that same year, but the final two did not appear until 1857. Impromptu No. 1 in C Minor is marked by unusual focus and compression. It is built largely on the quiet unaccompanied melody heard at the very beginning, and then developed in quite different ways. This impromptu has no clearly defined trio section, but Schubert introduces beautifully contrasting lyrical secondary material. Especially remarkable are the harmonic progressions on the final page, where the music works its graceful way to an almost silent close in C major. No. 2 in E-flat Major is built on long chains of triplets that flow brightly across the span of the keyboard; the center section is stormy and declarative, and Schubert rounds the work off with a brief coda. In No. 3 in G-flat Major Schubert spins an extended, songlike melody over quietly rippling accompaniment; measure lengths are quite long here (eight quarters per measure) to match the breadth of his expansive and heartfelt melody. Throughout, one hears those effortless modulations that mark Schubert’s mature music. No. 4 in A-flat Major is built on a wealth of thematic ideas. The opening theme falls into two parts: first comes a cascade of silvery 16th notes, followed by six chords; Schubert soon introduces a waltz tune in the left hand. In the central section he modulates into C-sharp minor and sets his theme over steadily pulsing chords before the music makes a smooth transition back to the opening material and concludes brightly.

On October 1, 1853, the 20-year-old Brahms appeared at the Schumann home in Düsseldorf and began to play the piano. Robert listened for only a few moments before he summoned his wife, and the two of them were enthralled. That night Clara wrote in her journal:

Here again is one of those who comes as if sent straight from God. He played us sonatas, scherzos etc. of his own, all of them showing exuberant imagination, depth of feeling, and mastery of form. . . . It is really moving to see him sitting at the piano, with his interesting young face which becomes transfigured when he plays, his beautiful hands, which overcome the greatest difficulties with perfect ease (his things are very difficult), and in addition these remarkable compositions.

In a notice published later that month, Robert hailed the young composer: “Sitting at the piano he began to disclose wonderful regions to us. We were drawn into even more enchanting spheres. Besides, he is a player of genius who can make of the piano an orchestra of lamenting and loudly jubilant voices. There were sonatas, veiled symphonies rather . . .”

The first work Brahms played for the Schumanns was his Piano Sonata in C Major, which he had completed in January of 1853, four months before his 20th birthday. Brahms published this sonata later that year as his Opus 1 even though several works written earlier were assigned higher opus numbers, and he was honest about his reasons: he was proud of this music and wanted his first published work “to appear in the most favorable light.”

In a famous remark, Brahms spoke of his anxiety over working in the shadow of Beethoven and of “how the tramp of a giant like him” haunted his efforts to compose a symphony. The very young Brahms was no less aware of the example of Beethoven’s piano sonatas, and everyone feels the similarity between the opening of Brahms’s Sonata in C Major and Beethoven’s Hammerklavier Sonata: the rhythm is identical, and the openings make the same broad and dramatic gesture. But the teenaged composer is already in possession of his own voice, and this sonata is unmistakably the music of Brahms rather than an imitation of Beethoven. It is a big-boned work in four substantial movements, and it stretches out to over half an hour in performance. Already evident are many of the trademarks of Brahms’s piano music: rolled chords, frequent use of the piano’s ringing high register, rhythmic complexities, a particular fondness for passages written in thirds, extensive octave and chordal writing, and moments of such power that they seem to confirm Schumann’s assertion that these early sonatas were really “veiled symphonies.”

The opening Allegro is in a broad sonata form: the dramatic beginning gives way to extensive and varied secondary material, which Brahms specifies should be both dolce and con espressione; much of the development, in fact, treats this lyric material before the movement pounds to its dramatic close. The second movement is in variation form, and Brahms uses as his theme a melody that he believed an old German folksong: he writes the words of the song into the piano score and treats this line as if it were being sung by a soloist who is answered by a chorus. The four variations, all decorative, grow increasingly complex, and along the way Brahms breaks the metric flow down into such unusual units as measures of 3/16 and 4/16. This movement proceeds without pause into the Scherzo, appropriately marked Allegro molto e con fuoco, which gallops along in 6/8 meter. The relatively cheerful mood of its beginning is gradually left behind as the music approaches the end of the opening section, and again Brahms’s markings tell the tale. He moves from feroce to fortissimo and molto pesante, proceeds just as quickly to staccatissimo e marcato, and pounds home on a cadence marked strepitoso (“noisy”) that seems to end in the middle of nowhere on stark E-minor chords. The flowing trio section makes a similar progression, moving from its restrained and melodic opening through a powerful climax; a sudden rip down the scale plunges us back into the opening material and a da capo repeat. The finale is in rondo form, and its opening theme is a variant of the opening gesture of the first movement, now rebarred into 9/8 and featuring some wonderfully unexpected accents as its rips along. There are two major episodes along the way, and the sonata dances its way to an ebullient close on a lengthy coda, now in 6/8, that Brahms marks Presto non troppo ed agitato.

This youthful sonata had some distinguished performances in its early years, occasions when it would have been fun just to have been there and watch and listen. These include not only Brahms’s private performance for Robert and Clara Schumann, but also a performance of the first movement in Hamburg by the young Hans von Bülow in 1854, and—maybe best of all—the performance that Franz Liszt sight-read from Brahms’s manuscript when the young composer visited him at Weimar in the summer of 1853.

Listen

Buy Music

![]()

The Dante Sonata and other worksBuy Now

![]()

Rachmaninov: Piano Concerto No.3, Rhapsody on a Theme of PaganiniBuy Now

Steinway Society The Bay Area is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com