- About

- Program

- Program Notes

- Listen

- Buy Music

About

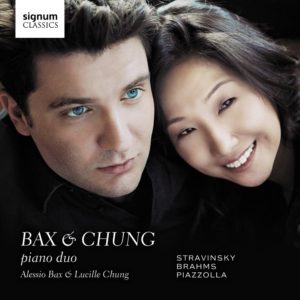

UK magazine Together calls husband and wife team Alessio Bax and Lucille Chung one of the most “appealing and impressive piano duos of our time.” They have performed in major festivals and concert halls around the world. The couple met at Japan’s Hamamatsu Competition, where Bax says, “I think we fell in love with each other’s playing!” The duo’s three CDs feature works of Saint-Saëns, Stravinsky, and Ligeti for piano four-hands and two pianos. Recent performances include Lincoln Center; Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, DC; and Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires.

Program

- Allegro molto moderato

- Largo

- Allegro vivace

- Tempo I

- En bateau (“Sailing”) (Andantino)

- Cortège (“Procession”) (Moderato)

- Menuet (Moderato)

- Ballet (Allegro giusto)

- The Shrovetide Fair

- Petrushka’s Room

- The Moor’s Room

- The Shrovetide Fair (Toward Evening)

Program Notes

The Fantasie in F Minor for Piano Four-Hands is one of the creations of Schubert’s miraculous final year of life, which saw a nearly unbroken rush of masterpieces. Schubert wrote most of the Fantasie in January 1828 but ran into problems and set the work aside for several months, returning to complete it in April. He and his friend Eduard von Bauernfeld gave the first performance on May 9 of that year, six months before the composer’s death at age 31.

Music for piano four-hands is a very particular genre, now unfortunately much out of fashion. In early 19th-century Vienna, however, there was a growing market for music that could be played in the home, where there might be only one piano but several pianists, usually amateur musicians. Such music often had an intentionally social appeal—it was not especially difficult, and it tended to be pleasing rather than profound. Much of Schubert’s four-hand piano music was intended for just such home performers (he often wrote music for his students to play together), but the Fantasie in F Minor is altogether different: this work demands first-class performers and contains some of the most wrenching and focused music Schubert ever wrote. Schubert scholar John Reed has gone so far as to call it “a work which in its structural organisation, economy of form, and emotional depth represents his art at its peak.”

The title fantasie suggests a certain looseness of form, but the Fantasie in F Minor is extraordinary for its conciseness. Lasting barely a quarter of an hour, it is in one continuous flow of music that breaks into four clear movements. The very beginning—Allegretto molto moderato—is haunting. Over murmuring accompaniment, the higher voice lays out the wistful first theme, whose halting rhythms and chirping grace notes have caused many to believe that this theme had its origins in Hungarian folk music. Schubert repeats this theme continually—the effect is almost hypnotic—and suddenly the music has slipped effortlessly from F minor into F major. The second subject, based on firm dotted rhythms, is treated at length before the music drives directly into the powerful Largo, which is given an almost baroque luxuriance by its trills and double (and triple) dotting. This in turn moves directly into the Allegro vivace, a sparkling scherzo that feels like a very fast waltz; its trio section (marked con delicatezza) ripples along happily in D major. The writing for the first pianist here goes so high that much of this section is in the bell-like upper register of the piano—the music rings and shimmers as it races across the keyboard. The final section (Schubert marks it simply Tempo I) brings back music from the very beginning, but quickly the wistful opening melody is jostled aside by a vigorous fugue derived from the second subject of the opening section. On tremendous chords and contrapuntal complexity the Fantasie drives to its climax, only to fall away to the quiet close.

Schubert dedicated this music to the Countess Caroline Esterházy, who 10 years before—as a girl of 15—had been one of his piano students. Evidence suggests that Schubert was—from a distance—always thereafter in love with her: to a friend he described her as “a certain attractive star.” Given the intensity of this music, it is easy to believe that his love for her remained undiminished in the final year of his life.

In 1886, Claude Debussy—unknown to the world at large but only too well known to the authorities at the Paris Conservatory—began work on a set of pieces for piano, four-hands. This was a difficult time for the 24-year-old composer. He was just completing two unhappy years in Rome, where he had been obligated to study as winner of the Prix de Rome, and he would continue to struggle in obscurity for several more years. Not until 1893 and 1894, with the premieres of his String Quartet and Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun, did he achieve fame. Now, however, the young composer was writing for piano. He composed the two Arabesques in 1888, and the following year he completed the set of pieces for four-hand piano, which he published under the title Petite suite. There was a market for this sort of attractive music that talented amateurs might play at home, but the Petite suite became much better known nearly 20 years later when Debussy’s friend, the composer Henri Büsser, arranged it for small orchestra in 1907. Debussy himself conducted the orchestral version with some success, including a performance in Vienna; and the composer’s biographer Edward Lockspeiser notes that the orchestral version of Petite suite has achieved “an enviable place in the repertory of so-called light music.”

Critics have been hard on the suite, perhaps because it is still early Debussy and does not show the distinctive advances in harmony and form that mark his mature music. Lockspeiser, in fact, speaks of this music’s “period prettiness” and hears a number of echoes of earlier French composers in the four pieces. Despite the critics, the Petite suite has proven popular with audiences, and at least one of its movements has become famous on its own. This is the suite’s opening movement, En bateau—“In a Boat” or “Sailing”—which is also a favorite of pianists in its version for solo piano. It is in the form of a barcarolle, the gently rocking song of the Venetian gondoliers. Like all the pieces in Petite suite, it is in ternary form: an opening section, a middle section of different mood and harmony, and a return of the opening material that also subtly recalls music from the central episode. En bateau is in the manner of a Monet water painting, with brightly colored water lilies and brilliant sunlight glistening off the water’s surface. Debussy called the second movement Cortège, but there is little of the funeral procession about this movement, which rides along a steady pulse of 16ths in its outer sections. The third movement is a minuet that concludes very delicately, while the finale, called Ballet, dances with unusual energy. Its central episode also dances, but in a different way: Debussy marks this Tempo di Valse, and this music does waltz along its 3/8 meter before the opening material returns to drive the Petite suite to a powerful close.

Petrushka, Stravinsky’s ballet about three puppets at a Russian Shrovetide carnival, actually began life as a sort of piano concerto. In the summer of 1910, shortly after the successful premiere of The Firebird, Stravinsky started work on a ballet about a pagan ritual sacrifice in ancient Russia. But he set the manuscript to The Rite of Spring aside when he was consumed by a new idea: “I had in my mind a distinct picture of a puppet, suddenly endowed with life, exasperating the patience of the orchestra with diabolical cascades of arpeggi. The orchestra in turn retaliates with menacing trumpet-blasts. The outcome is a terrific noise which reaches its climax and ends in the sorrowful and querulous collapse of the poor puppet.”

When impresario Serge Diaghilev visited Stravinsky that summer in Switzerland to see how the pagan-sacrifice ballet was progressing, he was at first horrified to learn that Stravinsky was doing nothing with it. But when Stravinsky played some of his new music, Diaghilev was charmed and saw possibilities for a ballet. With Alexander Benois, they created a story line around the Russian puppet theater, specifically the tale of Petrushka, “the immortal and unhappy hero of every fair in all countries.” Stravinsky composed the score to what was now a ballet between August 1910 and May 1911, and Petrushka was first performed in Paris on June 13, 1911, with Nijinsky in the title role.

From the moment of that premiere, Petrushka has remained one of Stravinsky’s most popular scores, and the source of its success is no mystery: Petrushka combines an appealing tale of three puppets, authentic Russian folk tunes and street songs, and brilliant writing for orchestra. The music is remarkable for Stravinsky’s sudden development beyond the Rimsky-inspired Firebird, particularly in matters of rhythm and orchestral sound. One of those most impressed by Petrushka was Claude Debussy, who spoke with wonder of this music’s “sonorous magic.”

On this recital Petrushka is heard in an arrangement, apparently made by Stravinsky himself, for piano four-hands. A brief summary of the music and action, which divides into four tableaux separated by drumrolls:

First Tableau: The Shrovetide Fair To swirling music, the curtain comes up to reveal a carnival scene in 1830 St. Petersburg. The crowd mills about, full of organ grinders, dancers, and drunkards. An aged magician appears and—like a snake charmer—spins a spell with a flute solo. He brings up the curtain in his small booth to reveal three puppets: Petrushka, the moor, and the ballerina. At a delicate touch of the magician’s wand, all three spring to life and dance before the astonished crowd to the powerful Russian Dance. A drumroll leads to the second tableau.

Second Tableau: Petrushka’s Room This tableau opens with Petrushka being kicked into his room and locked up. The pathetic puppet tries desperately to escape and despairs when he cannot. Stravinsky depicts his anguish with two clarinets, one in C major and the other in F-sharp major: their bitonal clash has become famous as the “Petrushka sound.” The trapped puppet rails furiously but is distracted by the appearance of the ballerina, who enters to a tinkly little tune. Petrushka is drawn to her, but she scorns him and leaves.

Third Tableau: The Moor’s Room Brutal chords take us into the moor’s opulent room. The ballerina enters and dances for the moor to the accompaniment of cornet and snare drum. He is charmed, and the two waltz together. Suddenly Petrushka enters (his coming is heralded by variations on his pathetic clarinet tune), and he and the moor fight over the ballerina. At the end, the moor chases him out.

Fourth Tableau: The Shrovetide Fair (Toward Evening) At the opening of the tableau, a festive crowd swirls past. There are a number of set pieces here: the Dance of the Nursemaids, The Peasant and the Bear (depicted respectively by squealing clarinet and stumbling tuba), Dance of the Gypsy Women, Dance of the Coachmen and Grooms (who stamp powerfully), and Masqueraders. At the very end, poor Petrushka rushes into the square, pursued by the moor, who kills him with a slash of his scimitar. As a horrified crowd gathers, the magician appears and reassures all that it is make-believe by holding up Petrushka’s body to show it dripping sawdust. As he drags the slashed body away, the ghost of Petrushka appears above the rooftops, railing defiantly at the terrified magician, who flees. Petrushka’s defiance is depicted musically by the triplet figure associated with him throughout. Quiet strokes of sound, taken from both the C-major and F-sharp major scale, bring the ballet to an end that is—dramatically and harmonically—ambiguous.

Libertango for Piano Four-Hands (arr. Bax/Chung)

Astor Piazzolla was a fabulously talented young man, and that wealth of talent caused him some confusion as he tried to decide on a career path. Very early he learned to play the bandoneon, the Argentinian accordionlike instrument that uses buttons rather than a keyboard, and he became a virtuoso on it. He gave concerts, composed a film soundtrack, and created his own bands before a desire for wider expression drove him to the study of classical music. In 1954 he received a grant to study with Nadia Boulanger in Paris, and it was that great teacher who advised him to follow his passion for the Argentinian tango as the source for his own music. Piazzolla returned to Argentina and gradually evolved his own style, one that combines the tango, jazz, and classical music. In his hands, the tango—which had deteriorated into a soft, popular form—was revitalized. Piazzolla transformed this old Argentinian dance into music capable of a variety of expression and fusing sharply contrasted moods: his tangos are by turn fiery, melancholy, passionate, tense, violent, lyric, and always driven by an endless supply of rhythmic energy.

Alberto Rodríguez Muñoz (1915–2004) was an Argentinian poet, playwright, and stage director. In 1962 he staged his play El tango del ángel, in which an angel descends into the slums of Buenos Aires and cleanses the souls of the poverty-stricken inhabitants but is eventually killed in a knife fight. Piazzolla supplied incidental music for the play, and among those pieces was his Milonga del ángel. A milonga is a dance that originated in the Argentina-Uruguay area in the 19th century; originally fast, it has been described as a forerunner of the tango. Piazzolla’s Milonga del ángel, however, is in a slow tempo, and it has become one of his best-known compositions, arranged for many different instrumental ensembles. Its haunting beginning gives way to a more animated central episode (in Piazzolla’s recording of the piece, this section featured a memorable violin solo); this rises to a climax and drives to the firm close.

After returning from his studies with Nadia Boulanger in Paris, Piazzolla had great success in Argentina, but after two decades there (and a heart attack in 1973), he decided to return to Europe. Libertango, composed in Italy in 1974, quickly became a hit in Europe, and it remains today one of Piazzolla’s most popular works. The title of this brief tango is somewhat fanciful (Piazzolla himself described it as “a sort of song of liberty”), and listeners will be taken more by its pulsing rhythm, which functions as an ostinato throughout, and Piazzolla’s sinuous, sensual, and dark main theme.

Listen

Buy Music

Steinway Society The Bay Area is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com