About

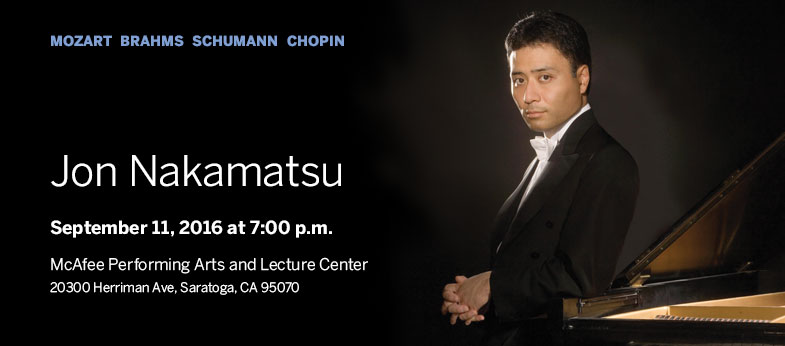

Jon Nakamatsu grew up in San Jose, graduated from Stanford University and his wife teaches at Saratoga High School. Though his busy touring schedule often keeps him away, he is immensely popular with the Bay Area audiences. A true aristocrat of the keyboard, whose playing combines elegance, clarity, and electrifying power, Nakamatsu is noted for his continuously expanding career based on a deeply probing and illuminating musicality, as well as his quietly charismatic performing style.

Since his dramatic 1997 Van Cliburn Gold Medal triumph, Jon Nakamatsu’s brilliant but unassuming musicianship and eclectic repertoire have made him a clear favorite throughout the world, both on the concert circuit and in the recording studio. He has performed widely in North America, Europe, and the Far East. Mr. Nakamatsu has been soloist with many leading orchestras, including those of Detroit, Los Angeles, Rochester, San Francisco, Seattle, Tokyo and Vancouver. Numerous festival engagements have included the Aspen, Tanglewood, Ravinia, Vail, and Britt festivals. In 1999, Mr. Nakamatsu performed at the White House for President and Mrs. Clinton.

Mr. Nakamatsu records exclusively for Harmonia Mundi USA, which has released 12 critically acclaimed CDs. His all-Gershwin recording featuring Rhapsody in Blue and the Concerto in F rose to number three on Billboard’s classical music charts, earning extraordinary critical acclaim.

Jon Nakamatsu studied privately with the late Marina Derryberry from the age of six, and has worked with Karl Ulrich Schnabel, son of the great pianist Artur Schnabel. Mr. Nakamatsu is a graduate of Stanford University.

Program

“Day has gone and the moon has come;

She sees two hearts in love made one

That blissfully cling together”

Program Notes

Although the publication date of Mozart’s Piano Sonata No. 13 is 1784, a mystery surrounds the composition date, with various pieces of evidence, from the style to maturity to the paper on which the manuscript was written, all suggesting an earlier date. The first movement Allegro opens with a cheerfully charming tone and remains true to the sonata form, while still affording the pianist opportunities for personal flourishes and light touches through tremolo (rapid reiteration of a note). The Andante trades in the airy feeling for deep expression, with chromaticism to evoke slight dissonance. The opening theme returns for the third and final movement, but is now punctuated with broken chords and rapid movement that build to the finale and climax, where major and minor keys alternate in seconds and a pause signals the theme’s final repeat.

One would easily be confused by seeing five movements listed for a sonata, a composition form usually limited to at most four, and indeed it is anomalous because Brahms included this sonata’s Intermezzo as a bonus. This big piece certainly does not waste time – the entrance is drenched in fortissimo chords, which makes sense given Brahms’ great respect for Beethoven. The “fate” motif from Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony can be heard throughout three of the five movements, with the bonus Intermezzo “Ruckblick” (“Looking Back” or “Retrospection”) featuring it heavily. At this time (1853), Brahms was only twenty years old and was more famous as a pianist than a composer, but his unique ability to contrast soft and bold themes within a single movement was apparent even to mature composers in his circle, such as Robert Schumann. That talent and tendency culminates in a finale that intertwines marches, lyrical melodies, sprightly steps and brilliant showiness.

Here we have another piece written by a budding, twenty-year-old composer. Schumann found himself so entranced by Jean Paul’s unfinished novel Flegeljahre (“The Awkward Age”) that he began composing on the piano to depict its final scene, which takes place at a masked ball. In Papillons (“Butterflies”) each movement signifies a dance, with an essential polonaise in the eleventh movement to represent a confession of love in the Polish language by Wina, who has captured the hearts of the novel’s two main characters, brothers Walt and Vult. In fact, only the last two movements were written after Schumann had finished reading the novel, and therefore contain direct references to its final chapter, a masked Ball at which Vult tricks Wina into confessing her love for Walt and then departs. Schumann was partial to these themes and this style of conveying story and emotion. The themes are reused and even explicitly acknowledged a few years later in one of his most prominent works, Carnaval, Op. 9.

These three selections, composed by Chopin between 1832 and 1842, are all famous for being difficult to perform. The Scherzo No. 3 overflows with energy that builds throughout its octave chords, delicate arpeggios, precise figures and lyrical melodies. These fast patterns, especially during the climax, occupy the pianist fully. The Nocturne in F-sharp Major feels slower and calmer, with its 2/4 time signature, but the ornamentation and the eighths and dotted eighths in the bass present a challenge to the pianist. The Polonaise in A-flat Major needs no introduction; this triumphant and transformative work, famously referred to as the “Heroic Polonaise,” has been a concert favorite since its introduction. From the opening chromatic fourths to the main dance theme with pounding left hand octaves to a momentous march, the pianist journeys across the piano’s entire vocal range before signaling the end with resounding chords.